Twelve ways to identify dangerous political rhetoric

11 March 2023

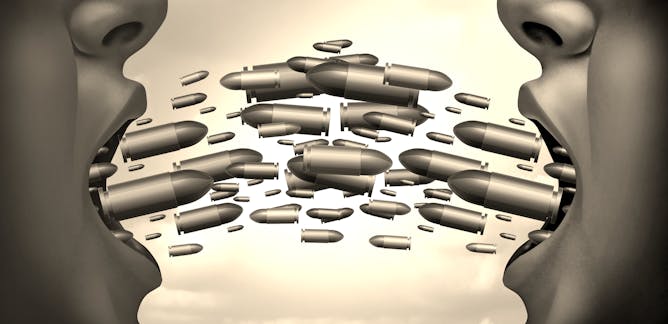

In the wrong hands, political rhetoric becomes a weapon, a tool of oppression and a divisive wedge wielded with merciless precision. We must always be vigilant to recognise the insidious tactics employed by those who would use our language to deceive and manipulate ourselves and others.

Here then are twelve ways to identify dangerous political rhetoric which can be used to divide, deride and destroy human rights:

- Be wary of language which pits one group against another. “Hardworking taxpayers versus lazy benefit claimants” creates an ‘us versus them’ mentality. It aims to portray one group as superior or inferior to the other, when in reality, they are equal human beings.

- Listen for language that dehumanizes groups by referring to them as animals. You may hear words such as “vermin,” “cockroaches,” or “billions of invaders” used to describe immigrants and aims to both instil fear and portray the suffering as something less than human which needs to be “eradicated”.

- Listen for language which delegitimizes the knowledge of experts while legitimizing the pseudo-knowledge of politicians. Conservative MP Michael Gove once claimed “people in this country have had enough of experts”. Not so, instead these sweeping statements aim to oppress opinions counter to those held by the ruling powers.

- Listen for language which creates scapegoats. The ammunition of a culture war is often aimed at the easiest target and weakest minority. Politicians and media outlets may blame LGBT+ people, immigrants or the poor for all your problems but never their policies.

- Listen for language which talks of “disease”. We are deeply scared of illness because it makes us weak. Therefore, some may claim that a particular group are “bringing diseases into our country”. This suggests that even the mere presence of this group is dangerous to you, when in reality they are of no threat whatsoever.

- Listen for the language of violence and war. Again often used against immigrants, you may hear words such as “killers”, “gangs”, or statements such as “we need to win the war against (group)” which all suggest that the innocent are armed, dangerous and intending to harm you.

- Listen for language which suggests a conspiracy. Phrases such as “the mainstream media is hiding the truth” or “the experts are working against us” or a more recent American-centric introduction “the liberal elite” create a sense of distrust and paranoia. Making you question everything is the first way to have you trust nothing.

- Listen for the language of authoritarianism. Politicians often use euphemisms to soften their language and make their ideas more palatable. “Strong and stable government” may sound sensible, but it could also mean authoritarian and unaccountable.

- Listen for language which plays on emotions rather than logic. Politicians often say “we need to do x for the sake of our children” because it’s emotionally compelling and hard to argue against, but that doesn’t always mean what they are proposing is either a logical or correct solution to a complex problem.

- Listen for language which belittles alternative opinions and attacks the other side. Quips such as “Fake News” or names such as “Remoaners” are used to discredit legitimate criticism and create a false sense of consensus. If someone is attacking the group, it’s often because they can’t debate their ideas.

- Listen for language which portrays legitimate criticism of an idea or person as an attack on the country or democracy. You may hear phrases such as “this investigation (against our idea or actions) is an attack on democracy” which aims to portray critics as enemies.

- Lastly, examine the slogans; “Stop the Boats” is a complex problem trying to be summarized into a three-word solution. You cannot summarize a life event into a tricolon of three words without first removing all the important details.

This is not a comprehensive list and there are many more examples of language such as this. But as alarmist as this may sound, knowing how to identify the language of authoritarianism is often one of the first steps towards preventing the goose-stepping which can later follow.

As written by Martin Niemöller:

First they came for the Communists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Communist

Then they came for the Socialists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Socialist

Then they came for the trade unionists

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a trade unionist

Then they came for the Jews

And I did not speak out

Because I was not a Jew

Then they came for me

And there was no one left

To speak out for me.